It is sometimes said that, “the People made the American Revolution!” People’s histories begin with a complaint that historians have taken the Revolution from the people who made it and credited it to those few “founders” who are etched in stone, marble and our textbooks. People’s histories redress this injustice by developing two useful but limiting ideas: first, that one could not make a successful revolution without the power that comes with the support of a very broad spectrum of ‘the people;’ second, that the success of the Revolution depended quite crucially upon the resistance that emerged locally, whether on the farmsteads or plantations that made upon the vast majority of America or within the urban ‘crucibles’ of revolution scattered along the coast of British America.

Of course there is a romance to the idea of the People leading the revolution from below. The idea is beautifully represented by Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, an allegorical representation of the French revolution of July 1830. Although the figures in the painting are represented with details that allow us to read their social position, these hallmarks of mid-nineteenth century realism don’t dispel the question of how these people ended up on the barricade following this beautiful bare-breasted “Liberty.” But it seems certain that “Liberty” has tipped the scales of justice and allowed the downtrodden finally to prevail over the oppressors. The idea of the spontaneous movement of the people toward freedom is co-implicated with the Romantic concept of the nation where the “folk” are the well-spring of the nation. National revaluation of ‘the People’ gains expression in the ballad rival of the late eighteenth century, the study of regional dialects, the collection of the local legends and the creation of myth-laden Wagnerian opera. What is missing from this picture? Politics has been erased from revolution. People’s histories have a way of dispensing with the endless talk about ends and means, the painfully protracted negotiation about representation, sovereignty and unity. In other words, part of the romance of the People leading the Revolution comes from bypassing what Pauline Maier has called the “grubby work of politics.”

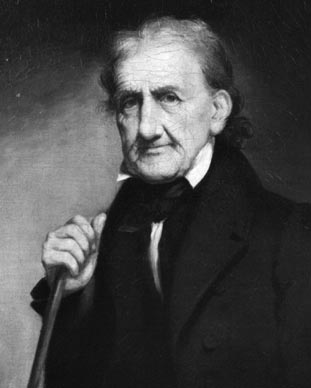

“The People”: the definite article seems to establish their unity and singularity. But which people? Who gets to be part of the People? People’s histories are by design inclusive: the People include women, young apprentices, common laborers, itinerants, black slaves and sometimes even Native Americans. When done most effectively, as in Gary Nash's The Unknown American Revolution (2005), a people's history can valuably expand the scope of participants in the Revolution. Most of these histories also accept a wide spectrum of the middling ranks of farmers, craftsmen, and tradesmen. But how does one define the people so that it does not become tendentious? Most People’s histories explicitly exclude elites of various sorts—big landowners, merchants, lawyers, ministers, and others. These histories usually solve this nagging problem by zooming in to a few individuals, “ordinary people,” farmers, craftsmen, shoe-makers (like George Hewes pictured at right) who are filled out with rich detail, are quoted in their plain but vivid language, so they become epitomes of “the People.” This ends simplifying and abstracting the agents of history in a fashion that is oddly like founders’ histories.

Rather than accepting magical political efficacy of “the People,” peoples’ histories should be read to understand one of the most remarkable achievements of the American Revolution: how a very broad spectrum of people—Whig elite, farmers, craftsmen and day laborers—came to act together as mediators of revolution. This, for example, is one way to describe what was achieved on the day the tea was destroyed in Boston harbor. By mobilizing people of every rank, it became the “largest mass action of the decade,” “a quasi-military action,” “the most revolutionary act of the decade” (Young 1999, 99-107) and enormously popular. This points to three discoveries: First: people’s histories suggest that “ordinary people” fought Britain in the name of the same causes as the Whig leadership in places like Boston and Williamsburg did: taxation, consent, sovereignty, loss of liberty, etc. Thus when the farmers of Hubbardstown Massachusetts wrote back to the Boston Committee on 23 March 1773, they insist: “We are of opinion that Rulers first Derive their power from the Ruled by certain laws, …”(Breen 2010, 243)

Second: the initiative of the Boston Committee of Correspondence was not, as Governor Hutchinson thought, manipulating “the people” like puppets. Instead the Boston Declaration provided the occasion for towns like Worcester and Brunswick (Maine) to hold meetings where local leaders would emerge, consider what they thought of the political crisis, and act together. (Raphael 2002, 37-38; Breen 2010, 45-51)

Thirdly: with the intensification of the American crisis, many towns and communities reject the old leaders and recruit new ones. From Worcester Massachusetts to Philadelphia there is a shift from Tories to Whigs, older to younger, more to less propertied. (Ammerman 1974, 65-115). Often the new leadership is of ambiguous rank, between the highly educated elite and the literate farmer or craftsman. Thus Matthew Patton of New Hampshire begins the Revolution as a prosperous farmer but ends serving as a probate judge (1776-1777) and the Governor’s Council (1778). (Breen 2010, 1-16) Changes in leadership made the revolution more popular, without it becoming the work of a great abstraction, “the People.”

Why when we study the Revolution should we divide the elite from the people, when it is clear that both were essential to the revolution? Some who were part of the elite (like Samuel Adams and Thomas Jefferson) worked to expand popular politics. Even John Adams, hardly a figure with strong populist credentials, took great pleasure when the popular committees displaced the Pennsylvania Assembly in May and June 1776. In describing the celebratory reading The Declaration of Independence, he writes: “The Declaration was yesterday published and proclaimed from that aweful stage in the State house Yard, by whom do you think? By the committee of safety!, the committee of inspection, and a great crowd of people…” In describing the defeat of anti-Independence men John Dickinson and Joseph Galloway in the recent election, Adams writes: “Thus you see the effect of men of fortune acting against the sense of the people” (John Adams to Samuel Chase: 9 July 1776; Adams 1979, 4: 372). |

"Liberty Leading the People" (1830)

"Liberty Leading the People" (1830)

By Eugène Delacroix

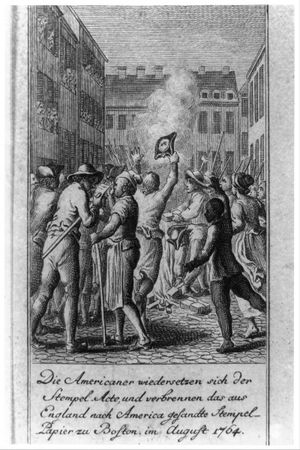

Cartoon of Stamp Act Agitation in Boston

George Robert Twelves Hewes, 1835.

|

![Protocols of Liberty: Communication, Innovation, and teh American Revolution [Book Banner from Title Page Image]](Images/William_Warner/Protocols_of_Liberty_Illustrations/Protocols of Liberty - Title Banner.png)

![Protocols of Liberty: Communication, Innovation, and teh American Revolution [Book Banner from Title Page Image]](Images/William_Warner/Protocols_of_Liberty_Illustrations/Protocols of Liberty - Title Banner.png)