There is a vast gap between how Whigs received the Declaration in July 1776 and how most Americans have known the Declaration of Independence in our own time. The Declaration of Independence is widely accepted to be one of the most influential political documents of the modern era, one that has been imitated at least 106 times in as many nations between 1776 and 1993. (Armitage, 2007, 145-155) For Americans it can have a more personal meaning as the birth certificate of the nation as well as its most resonant statement of our rights and liberties. Who are we to thank for this imperishable masterpiece? For most Americans the answer has been simple: it is Thomas Jefferson, the solitary genius of Monticello, who is the author of this monument of American liberty.

Because this framework obscures the actual role of the Declaration in mediating independence, it is worth posing a question. How did the idea of Jefferson’s authorship gain so much credibility? After all, the Declaration has none of the legal qualifications associated with authorship in the 18th century. Jefferson was not the originator of the composition; he did not write alone; and as drafter he and the drafting committee borrowed freely from others. In short, it would have been difficult for Jefferson to claim ownership of the document under the operative copyright law of the day, the 1710 Law of Queen Anne. So where does the notion of his authorship begin?

The seeds for Jefferson’s retroactive claim to authorship began a few days after the publication of the Declaration. As first drafter of the document, Jefferson was proud of his work and distressed by extensive changes made by Congress.

|

So, as a muted act of protest, Jefferson sent manuscript copies of his committee version of the Declaration (which had been submitted to Congress on 28 June) along with the final printed Dunlap version of the Declaration to both Richard Henry Lee, the source of the resolution, as well as to his old mentor and fellow member of Congress, George Wythe: “You will judge whether it is the better or worse for the critics.” (8 July 1776, TJ to RHL, Letters, II,2)

The story might have ended there. Only members of Congress knew that Jefferson was the primary drafter on the drafting committee, and most who read different versions of the Declaration, and understood the necessary collective compositional process of framing public documents, have judged that Congress’s final draft was superior to Jefferson’s or the committee’s. But, on April 30, 1819, Dr. Joseph McKnitt Alexander published in the Raleigh Register and North Carolina Gazette the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, supposedly adopted by the town of Mecklenburg North Carolina on 31 May 1775, after it had heard the news of the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord. Because it contains many striking echoes of the Declaration and because it was adopted a year before Congress’s declaration, this publication opened Jefferson to the charge of plagiarism.

What gave this charge special force was the sea-change that had overcome the concept of authorship in the half century since the Declaration. When Jefferson served as drafter of the Declaration, his care with the rhetoric, diction and rhythm of the Declaration (Fliegelman, Lucas, Wills) and his easy incorporation of the ideas and words of others confirms that he wrote under the influence of a neo-classical conception of the author. In 1776, striving for novelty could still open an author to the charge of immodesty, conceit and pride. Satirists like Pope and Swift had lambasted the modern commercial rage for novelty as the way shallow moderns turned their backs upon the enduring wisdom of ancient knowledge. This is why Pope could write in The Essay on Criticism (1710), that “True wit is nature to advantage dressed, / What oft was thought, but ne'er so well express’d” (Essay on Criticism, ll XX). But under the new protocols of Romantic authorship, as they had gained prominence by 1821, it was assumed that out of the mysterious original genius of the individual author would come not what “oft was thought,” but what was never thought before. |

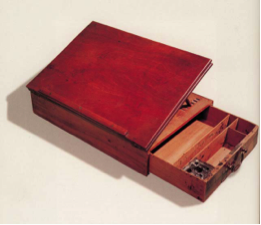

The portable writing desk and the house at the southwest corner of Market and Seventh Street in Philadelphia where Jefferson wrote early drafts of the Declaration in June 1776.

|

Forty years after independence many of the citizens of the young republic sought to honor the heroes of 1776. But there were good reasons not to honor them as “fathers,” for it conflicted with the very nature of a republic, where the people are sovereign. The term “founding fathers” would become standard by the early 20th century, but in the early 19th century the memory of monarchy discouraged the use of the terms like ‘father’ to describe political leaders. However, as the descendants of these founders undertook the editing of their papers and related public documents, the concept of authorship became the bedrock for conceptualizing the founders. It was the founders who had authored the nation, who owned its copyright, and Jefferson had started it all by authoring the Declaration of Independence. |

|

![Protocols of Liberty: Communication, Innovation, and teh American Revolution [Book Banner from Title Page Image]](Images/William_Warner/Protocols_of_Liberty_Illustrations/Protocols of Liberty - Title Banner.png)

![Protocols of Liberty: Communication, Innovation, and teh American Revolution [Book Banner from Title Page Image]](Images/William_Warner/Protocols_of_Liberty_Illustrations/Protocols of Liberty - Title Banner.png)