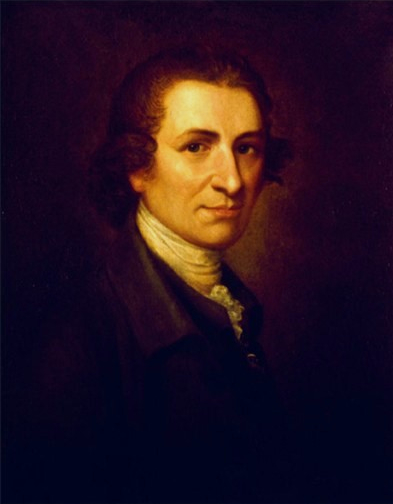

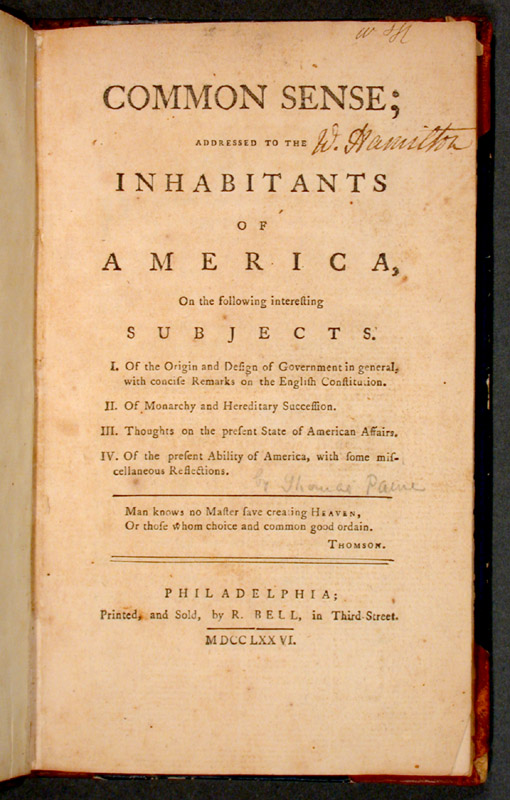

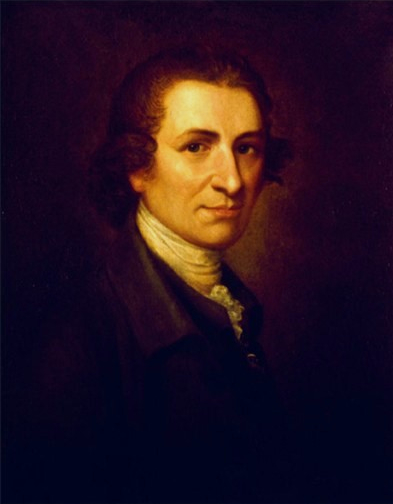

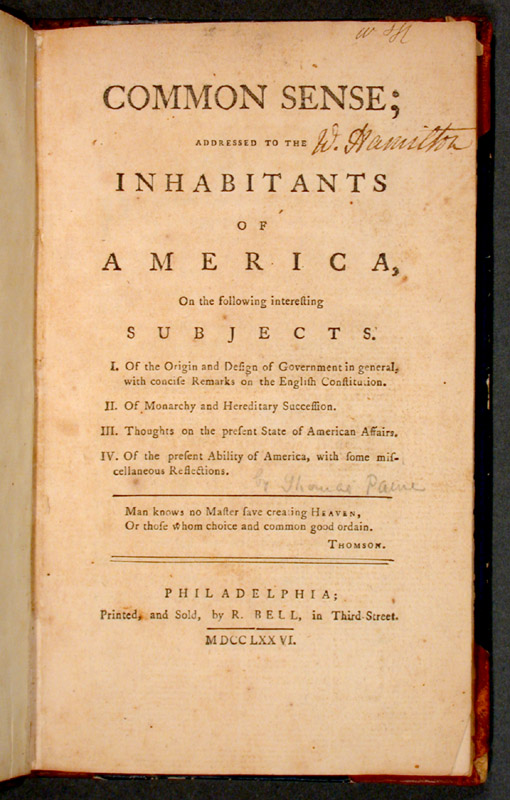

Within the historiography of the Revolution, Thomas Paine enjoys a dubious position. Long lauded as a heroic propagandist, Paine was credited with turning American popular opinion toward independence by publishing the first best-seller. However recent studies of the actual circulation of Common Sense have questioned this thesis. (Loughran, The Republic in Print, 2008) If one looks at the "SUBJECTS" listed on the title page of his pamphlet, a reader might expect a systematic treatise. Yet, once one starts reading one will find that Pained refused the generic expectations for the pamphlet: there is no apparent conceptual, historical, or rhetorical order to the argument. The pamphlet seems to be unsystematic by design. This may explain why John Adams was so dismayed by its popularity. Paine meanders through diverse topics, which offer occasions for memorable sound-bites like those found on right. It is worth pondering the art of the sound-bite, because it helps explain the how Common Sense became a harbinger of the democratic political culture of the coming centuries. Whenever the sound-bite incorporates into it bold bare statement a bit of with and a bit of the moral wisdom of a proverb, then the sound-bite is fit to enter the war of opinions without any of the tendium of the usual supports: facts, logic, history, or even knowledge. Instead, what the sound-bite achieves is a highly legible bit of 'common sense."

Paine’s practice of the political sound-bite may appear to be the very opposite of Jefferson’s concisely developed periods and carefully structured argument. However Paine’s epigrammatic statements offer another way to see things whole, not through the continuous view of a panorama, but through the foreshortening, concision, and aphoristic wit. Here commerce and politics blend with religion and entertainment. Positioned as we are in a rambling monologue—“I’ll tell you Friend…,” we are invited to savor these pithy statements. Paine developed a most economical way to take readers toward a millenarianism that mingles suspicion of government with a utopian summons, 'common sense' argument with political faith. Indulging in simplification as stark as the sloganeering of a contemporary ad campaign, Paine offers an anthology of sound-bits that may have help prepare Whig readers for the sublime vistas and authoritative pronouncements of the Declaration that was proclaimed in July 1776.

|

- Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness. (Paine 2004, 47)

- In England, a King hath little more to do than to make war and give away places. (61)

- But where, say some is the King of America? I’ll tell you Friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Britain. (75)

- There is something absurd in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island. (69)

- The independancy of America should have been considered, as dating its aera from, and published by, the first musket that was fired against her. (91)

- We have it in our power to begin the world again. (92)

|

|

|

![Protocols of Liberty: Communication, Innovation, and teh American Revolution [Book Banner from Title Page Image]](Images/William_Warner/Protocols_of_Liberty_Illustrations/Protocols of Liberty - Title Banner.png)