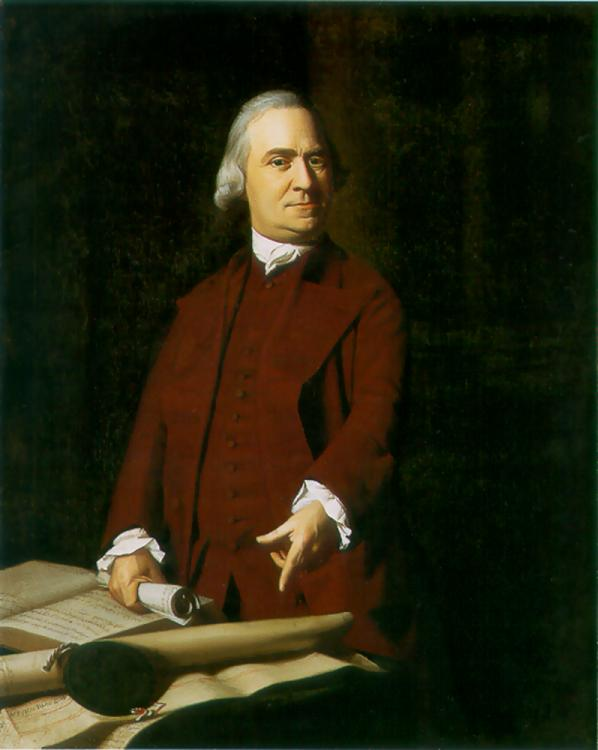

In John Singleton Copley's famous portrait of Samuel Adams, two terms are represented, an historical event (the 6th of March) and a person (Samuel Adams), so that each is fused and modified. Copley aligns the character of the individual Samuel Adams to a moment in the shared history of the town so that the moral resolve required for that moment, which is celebrated in the Boston Gazette of 12 March 1770 as the source of the town’s collective victory over the Governor, is now relocated to the face, expression and body of one man, Samuel Adams. Conversely, Samuel Adams is displaced out of the temporal scheme of portraiture, where a subject is placed in a time-out-of-time, assuming the posture of one at rest, or, alternatively, a subject who is caught in a particular instant (about to speak, rise, play with an object). By removing the subject from time as flux and change, the portrait painter usually subordinates transient psychological states to a representation of the fixed traits of character. Instead, Copley represents Samuel Adams as lodged within the historical moment that he then mediates. Situating Adams in this way has contradictory effects. On the one hand, it idealizes Adams as larger than life, one who can, because of his virtue, his strength and his will, master history. But on the other hand, this portrait withdraws Adams from the places, groups, and communication protocols through which he acted. What remains, and is glorified, is a mute gaze emanating from a powerful body; he is an apotheosis of restrained resolve, the peaceful determination of the Whig cause. This entails dissimulation: writing, as the residue of the networks, laws, institutions through which Adams (and many others) act is surmounted, so, through the fictional work of this portrait, Samuel Adams can rise up as the brave public personfication of the town. |

|

![Protocols of Liberty: Communication, Innovation, and teh American Revolution [Book Banner from Title Page Image]](Images/William_Warner/Protocols_of_Liberty_Illustrations/Protocols of Liberty - Title Banner.png)

![Protocols of Liberty: Communication, Innovation, and teh American Revolution [Book Banner from Title Page Image]](Images/William_Warner/Protocols_of_Liberty_Illustrations/Protocols of Liberty - Title Banner.png)